Discovering ancient cave art using 3D photogrammetry: pre-contact Native American mud glyphs from 19th Unnamed Cave, Alabama

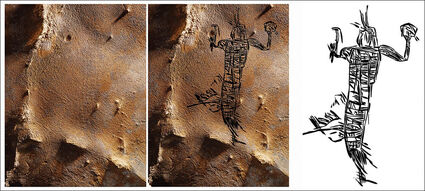

Anthropomorph in regalia (1.81m tall) from 19th Unnamed Cave, Alabama (photograph by S. Alvarez; illustration by J. Simek).

Since 1979, when the first cave art was documented in North America, dozens of other examples have come to light. Among these, 19th Unnamed Cave in Alabama contains hundreds of pre-contact Native American mud glyph drawings. In 2017, 3D modelling of the glyphs was initiated, ultimately enabling digital manipulation of the chamber space and revealing images that could not be perceived prior to modelling. Most surprisingly, the cave's ceiling features very large anthropomorphic glyphs that are not apparent in situ due to the tight confines of the cave. Cambridge argues that photogrammetry offers untapped potential for not simply the documentation but also the discovery of a variety of archaeological phenomena.

19th Unnamed Cave is the richest of all known cave art sites in south-eastern North America. First recognized to contain cave art in 1998, it contains hundreds of glyphs incised into the natural sediment coatings on the cave ceiling (Cressler et al. Reference Cressler1999). The pictures cover an area of nearly 400m2 in varying densities, from single figures to palimpsests of extensively superimposed engravings. While much of the imagery comprises abstract shapes and swirling lines, many representational figures are also worked into the sediment, including serpents, insects, birds and anthropomorphs (Figure 3a–b). Due to the low ceilings, most of these images, even though less than 1m in size, can only be viewed by lying on the cave floor. Thus, visibility of the cave art is constrained by the narrow confines of the cave itself, and the attenuated distance between the floor and ceiling limits perception of any larger images that might extend beyond the viewers' field of vision.

It should be noted that there is a detailed and widely disseminated map of the cave passages available, it is not shown here, as the cave is on private land, completely unprotected, and could be easily identified by vandals and looters.

All of the glyphs are incised into a natural, thin mud veneer on the cave ceiling that was produced and conserved by condensation corrosion (Tarhule-Lips & Ford Reference Tarhule-Lips and Ford1998). Most of the images comprise multiple lines that reflect the use either of human fingertips or an inscribing instrument composed of several parallel, rounded elements. A few glyphs were formed with a wider line scraped through the mud veneer using a flat-edged tool. Their first documentation of the glyphs in 1998 used still photography of all the individual images and more general photographs of wider areas of the ceiling. They also made a series of 20mm-wide cores into the floor sediments below the mud glyphs. While they did not map the entire glyph array, they did map the chamber outline and surface rocks, and located a number of individual glyphs using Cartesian coordinates. They examined the floor surface below the glyphs and documented all the artefacts found there.

Photogrammetry is a software-based 3D modelling technique. It begins with taking many photographs of a target object or location, with each photograph overlapping its neighbor by 60–80 per cent. Photogrammetry software compares the images and overlaps, and then calculates the camera positions used to produce the images. The software then triangulates the pixels in 3D space to create a point cloud. That cloud is rendered into a highly accurate mesh of the surface being modelled, and that mesh is skinned, or 'textured', with the original images to give a photorealistic 3D model. The result is then calibrated by measuring known distances. In 19th Unnamed Cave, we created three interlinked models: two of the engraved ceiling and a third model of the undecorated cave passages.

Over the course of two months of field work at 19th Unnamed Cave, they captured 16 000 photographs. Images for the overall cave model (the third model) were all taken first, using the on-camera flash, and shot both handheld and with a tripod. Following this, a 12-foot movable track was positioned at the edge of the engraved ceiling section.

The largest figure so far identified in 19th Unnamed Cave is probably that of a serpent (Figure 8). The head and body begin with a rounded top that grades imperceptibly into the torso and tapers to a pointed tail. The interior is filled with six parallel lines at the head and then diamond patterns to the tail that are formed by intersecting angled lines.

"As we have not seen their like before, we do not know the identity of these ancient cave art anthropomorphs. The most striking aspects of these cave art images are their size and context. Among the 19th Unnamed Cave mud glyphs are the largest cave art images known in North America. They are so large that the makers had to create the images without being able to see them in their entirety. Thus, the makers worked from their imaginations, rather than from an unimpeded visual perspective. These glyphs are similar in scale to the largest open-air rock art recorded in various contexts across the North American continent."

Anthropomorph in regalia (2.08m tall) from 19th Unnamed Cave, Alabama (photograph by S. Alvarez; illustration by J. Simek).

Published online by Cambridge University Press on May 4, 2022 and edited for space.

Reader Comments(0)