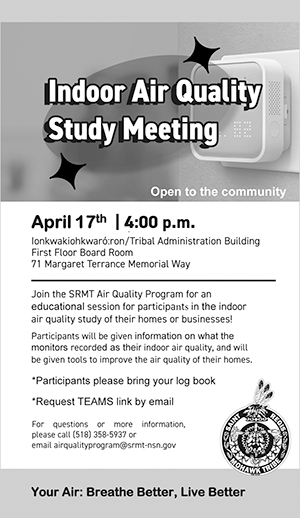

Ida's aftermath in Indian Country

Some Louisiana tribes and Native people were ‘very lucky’ and others weren’t

By Kallie Benallie. Reprinted with permission from Indian County Today.

Virginia Richard escaped Hurricane Ida just in time.

Richard, MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians, evacuated from the Ninth Ward of New Orleans on Aug. 28 to Austin, Texas. She reached out to many people asking if they were able to get out and if they were okay. As a result, she picked up a friend of a friend in the French Quarter and evacuated with them.

“I’m just extremely blessed and privileged to have gotten out,” she said.

Richard said is going to try to go back this weekend but definitely won’t return until she has power.

Power should be restored to almost all of New Orleans by Wednesday, 10 days after Hurricane Ida destroyed the electric grid, tearing down poles, transformers and even a massive steel transmission tower and leaving more than 1 million customers in Louisiana without power. That’s down from the peak of around 1.1 million five days ago as the storm arrived with top winds of 150 mph, tying it for the fifth-strongest hurricane ever to strike the mainland U.S.

Not every customer will have power back in the city, utility Entergy said in a statement Friday. Customers with damage where power enters their home will need to fix it themselves, and there could be some smaller areas that take longer.

And there still is no concrete promise of when the lights will come back on in the parishes east and south of New Orleans, which were battered for hours by winds of 100 mph or more, Entergy said.

The United Houma Nation, a state recognized tribe hit hard by the hurricane, said on Thursday it was working to get a mobile wi-fi tower to better communicate with citizens.

“We are still largely blind here on the ground except for cell and texting service,” the tribe posted on its Facebook page. The tower will help the tribe send text alerts to tribal citizens about available resources.

The tribe also asked its citizens to fill out a “check-in form” on the tribe’s website. To donate, click here. The tribe has roughly 17,000 tribal citizens residing in a six-parish service area.

Chief August “Cocoa” Creppel told Indian Country Today’s newscast on Aug. 30 that all six parishes got hit by the hurricane.

“We had sustained winds of 150 miles an hour for over 12 hours, and much of our community along with the Gulf is wiped out,” he said on the phone. “It looked like a bomb came in and just destroyed everything.”

As a firefighter for 40 years, Creppel said, “I have never seen this much destruction and disaster.” They aren’t able to get into some areas.

“It’s just hard as the chief to see this much disaster and the pain that my people are going through. There’s hardly anything we can do, but to help them out as much as we can, myself and our tribal council.”

The tribe has a donation fund setup on their website at: https://unitedhoumanation.org/

The storm missed the Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana by 25 miles, said the tribe’s chairman, Melissa Darden. The tribe is federally-recognized and located near the southern coast of Louisiana.

“We had some tropical storm winds, and a little rain, but we had no significant damage. We have a few tree branches down but that’s it,” she said. “We were very lucky, very blessed.”

Darden added they are trying to help tribal citizens who were in the affected areas and have sustained damage in New Orleans and Houma, which are more than 50 miles east of the tribe.

Many citizens of the Pointe au Chien Indian Tribe were safe from the predicted 12-foot-high surge from Hurricane Ida since they live in elevated structures, according to nola.com.

For the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, approximately two dozen citizens have evacuated. “The island has lost most of its land in recent decades due to rising seas, storms and erosion and is the focus of a federally funded relocation program,” reported nola.com.

There are four federally recognized tribes and 11 state recognized tribes in Louisiana.

Attempts to reach the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians in Mississippi were unsuccessful.

Mutual aid

Ashley Strongheart, Sugpiaq Nations, talked with friends in Louisiana and of the United Houma Nation. They told her about the flooding, limited gas and evacuations. When she asked them how she could help, one told her, “All we need is prayers, and we need help getting the word out for financial assistance for those who are affected by Ida.”

For that reason, she made the video to help Indigenous communities and because she also used to live in Louisiana and those communities helped her when she needed it.

Mutual aid networks are springing into action to supplement the more established relief services from federal and local governments, as well as larger charities.

The networks, in which community members pool resources and distribute donations to care for one another, seek to avoid the traditional charity model of giver and receiver. They grew in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic as communities across the country faced dire needs. And now they are mobilizing in the wake of other disasters like Hurricane Ida.

Another Gulf is Possible, a collective of 11 organizers and artists based in Louisiana, Texas and Florida had stored up 30 kits of solar panels, batteries, lanterns, power banks, iPads and water filters in preparation for the storm. They are gearing up to distribute the items to community organizers in New Orleans and the predominantly Native American communities of Grand Bayou and Grand Bois. But reaching people in some areas has been difficult because of the power outages, said Bryan Parras, a member of the group.

“People need everything,” said Anne White Hat, a Louisiana resident who’s part of the group, which has been collecting masks, goggles, and gloves to protect communities from mold or lead during clean-up efforts.

Ida’s miserable wake

Health officials received reports of people lying on mattresses on the floor, not being fed or changed and not being socially distanced to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, which is currently ravaging the state, Louisiana Department of Health spokesperson Aly Neel said. When a large team of state health inspectors showed up on Tuesday to investigate the warehouse, the owner of the nursing homes demanded that they leave immediately, Neel said.

Neel identified the owner as Bob Dean. Dean did not immediately respond Thursday to a telephone message left by The Associated Press at a number listed for him.

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards promised a full investigation and “aggressive legal action” if warranted.

Meanwhile, President Joe Biden was scheduled to visit Louisiana on Friday to survey the damage after promising full federal support to Gulf Coast states and the Northeast, where Ida’s remnants dumped record-breaking rain and killed at least 50 people from Virginia to Connecticut.

At least 13 deaths were blamed on the storm in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, including the three nursing home residents. Several deaths came in the aftermath of the storm from carbon monoxide poisoning, which can happen if generators are run improperly.

Tens of thousands still have no water in the midst of a sultry stretch of summer. Efforts continued to drain flooded communities, and lines for gas stretched for blocks in many places from New Orleans to Baton Rouge.

In the northeast

More than three days after the hurricane blew ashore in Louisiana, Ida’s rainy remains hit the Northeast with surprising fury on Wednesday and Thursday, submerging cars, swamping subway stations and basement apartments and drowning scores of people in five states.

Intense rain overwhelmed urban drainage systems never meant to handle so much water in such a short time — a record 3 inches in just an hour in New York.

On Friday, communities labored to haul away ruined vehicles, pump out homes and highways, clear away muck and other debris, restore mass transit and make sure everyone caught in the storm was accounted for.

Even after clouds gave way to blue skies, some rivers and streams were still rising. Part of the swollen Passaic River in New Jersey wasn’t expected to crest until Friday night.

“People think it’s beautiful out, which it is, that this thing’s behind us and we can go back to business as usual, and we’re not there yet,” New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy warned.

At least 25 people perished in New Jersey, the most of any state. Most drowned after their vehicles were caught in flash floods. At least six people were missing, Murphy said.

In New York City, 11 people died when they were unable to escape rising water in their low-lying apartments.

New York’s subways were running with delays or not at all. North of the city, commuter train service remained suspended or severely curtailed. In the Hudson Valley, train tracks were covered in several feet of mud.

Floodwaters and a falling tree also took lives in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and New York.

While the storm ravaged homes and the electrical grid in Louisiana and Mississippi, leaving more than 800,000 people without power as of Friday, it seemingly proved more lethal over 1,000 miles away in the Northeast, where the death toll outstripped the 13 lives reported lost so far in the Deep South.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Reader Comments(0)